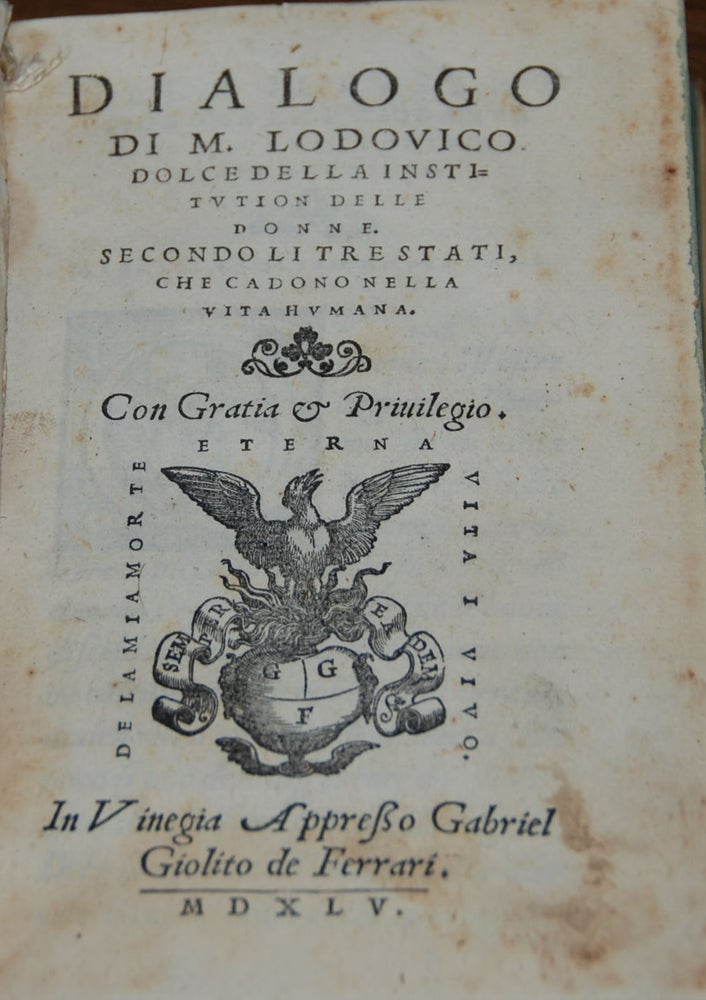

DIALOGO; della institution delle donne

Venezia: Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1545. First Edition. 8vo, 80 leaves, with printer's device on title page. Bound with:I quattro libri delle osservationi... Di nuovo da lui medesimo ricoretti, et ampliati, con le apostille. Sesta editione. 8vo. 240 pp. With the printer’s device on the title-page. Bound in 17th century vellum over boards, manuscript title on the spine, blue edges, entry of ownership on the title-page of the second work: Erdman p. 166. ‘Degli Sampericoli’, which had been thoroughly annotated by a contemporary hand (these annotations contain corrections and remarks on the Italian language and are slightly shaved), first title -page a bit stained, some foxing, but a very good, genuine copy. Venezia, Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1560. Item #56107

RARE FIRST EDITION of this treatise of conduct for women, which aimed to define the nature of women, their role in society and their behavior in everyday life. It adopts the tripartite division used since the Middle Ages by preachers in their sermons by status: unmarried girls, married women and widows (cf. H. Sanson, Introduction, in: “Lodovico Dolce, Dialogo della institutione delle donne”, Cambridge, 2015, pp. 1 “In 1545, Giolito published the Dialogo lella institution delle donne, by the poligrafo Lodovico Dolce, a close collaborator; it was republished in 1547, 1553, and 1560. Actually, it was a close adaptation of the Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives’s well -known De institutione feminae Christianae (1524), one of the first works exclusively treating women’s education and proper conduct. Vives’s treatise quickly became very popular throughout Europe, being translated into English, Dutch, French, German, and Italian (an original Italian translation by Pietro Lauro was published by Vincenzo Valgrisi in 1546). Although not directly dealing with the woman question, Vives rebutted the broadly held view that women were unable to engage in letters, but still drew a sharp division between women’s and men’s educational needs, stressing that women’s education aims at the safekeeping if their chastity and not a public life. Following most of Vives’s arguments and structure (three parts treating virginity, married life and widowhood respectively, Dolce transformed the treatise into a popular Italian genre of dialogue (between two fictional characters, Flaminio and Dorothea) and enriched it with specific Italian references and current events, such as a debate on marriage which is supposed to have taken place in Pietro Aretino’s house among Aretino, Fortunio Spira, Paolo Stresio, and the author. However, the most interesting difference between Vives and Dolce is found in their views on the appropriate reading for the young woman. Vives’s strong rejection of vernacular literature as immoral and lascivious could not have been adopted by Dolce, who approves non-lascivious vernacular literature, especially Petrarch and Dante. Dolce’s main concern as a poligrafo and collaborator of Giolito was to maximize the demand for vernacular literature by both men and women. It is probably within this context that Dolce omitted the term ‘Christian’ from the title in order to have greater latitude for initiative” (A. Dialeti, The Debate about Women in Sixteenth Century Italy, in: “Renaissance and Reformation”, XXVIII/4, 2004, pp. 11-12). Lodovico Dolce, a native of Venice, belonged to a family of honorable tradition but decadent fortune. He received a good education, and early undertook the task of maintaining himself by the pen. He offers a good example of a new profession made possible by the invention of printing, that of the ‘polygraph’ (poligrafo), in other words, the man of letters who made a living by working for a publisher, editing, translating and plagiarizing the works of others as well as producing some of his own. Thus Dolce for over thirty years worked as corrector and editor for the Giolito press. Translations from the Greek and Latin epics, satires, histories, plays.

The second work is listed as the the “sixth Edition" (but in fact the fifth). Dolce’s grammar of the vernacular was first published in 1550 as Osservazioni nella volgar lingua and then reprinted in 1552, 1556, 1558, 1560. Dolce aligned himself with the tradition established by grammarians of Northern Italy, beginning with Gian Giorgio Trissino and Rinaldo Corso. His goal was not to establish an abstract work but rather, through the description of the expressive value of specific form in context, to arrive at a series of grammatical notions. Dolce also accepted the current opinion to use as the standard the Tuscan used by the great authors of the fourteenth century. However, Dolce recognized that the languages live and grow and adapt themselves to contemporary circumstances. He therefore accepted as inevitable that Italian would be continually modified by the innovations of the men of letters from every region of the peninsula (D. Pastrina, La grammatica di Lodovico Dolce , in: “Sondaggi sulla riscrittura del Cinquecento”, P. Cherchi, ed., avenna, 1998, pp. 63 -73).Edit 16, CNCE 17365; Universal STC, no. 827098; Bongi, op. cit., II, p. 89 (exact reprint of the 1558 edition). - Thanks to Axel Erdman for his description of this book.

Price: $3,500.00 save 20% $2,800.00